The International Energy Agency (IEA) Is Engaged in Pure Propaganda on Behalf of the Big Green Grift

I’ve never been much of a fan of Art Berman, the petroleum geologist who was always making ‘peak oil’ sort of arguments about shale gas. Indeed, I have been inclined to the views of Jim Willis who wrote about Berman here and eight years later it sure looks like Jim was correct. But, Berman just came out with a devastating critique of the IEA, which sold its soul to the Big Green Grift company store. It exposes the ridiculous nature of that agency’s advocacy for energy transition and, this time, Berman is on very solid ground in my humble opinion.

The article is rather lengthy but here’s the important stuff:

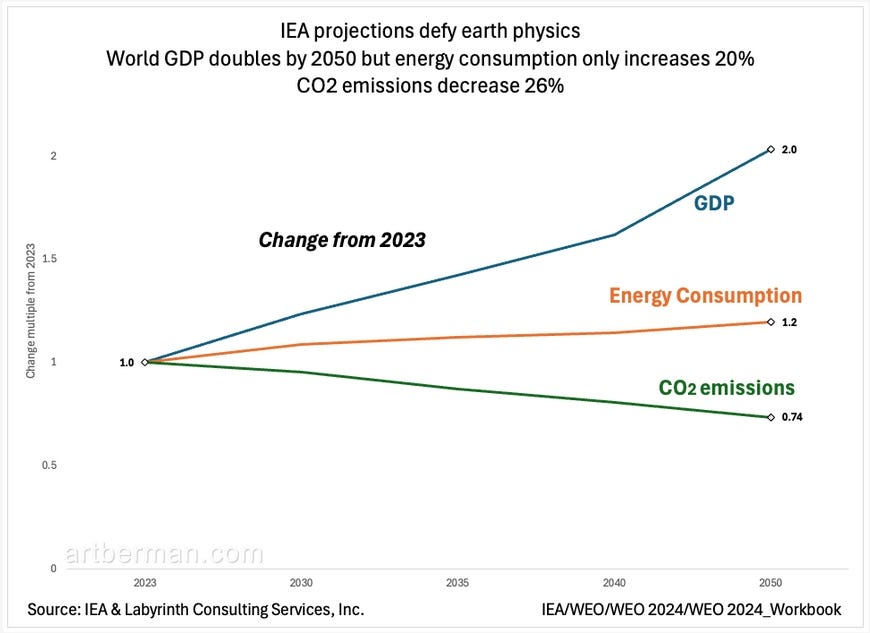

The big picture is that energy supply growth is set to slow to about one-third of the pace seen from 2010 to 2023, while consumption growth will decrease to two-thirds of its 2010 to 2013 rate. The catch? Global GDP (gross domestic product) is still expected to double by 2050 (Figure 6).

This disconnect highlights a fundamental problem—how can the economy expand with slower energy growth? GDP and energy consumption correlate almost perfectly so either the projections are wrong or the world economy is heading for a reality check.

The IEA partly explains the dilemma by pointing to a projected decrease in energy intensity—meaning less energy consumed per dollar of GDP added. This decoupling of energy consumption from economic growth assumes that technological advances and efficiency improvements will allow the economy to grow far beyond the limits imposed by energy use.

It’s a nice idea, but history shows that gains in efficiency often lead to more consumption, not less—a phenomenon known as the rebound effect or Jevon’s Paradox. Counting on continuous improvements in energy intensity is optimistic at best and misleading at worst.

GDP is often criticized as a distorted measure of economic growth for reasons beyond the scope of this post but a recent synthesis of decoupling summarized it this way.

“We conclude that large rapid absolute reductions of resource use and GHG emissions cannot be achieved through observed decoupling rates, hence decoupling needs to be complemented by sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets.”

A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions

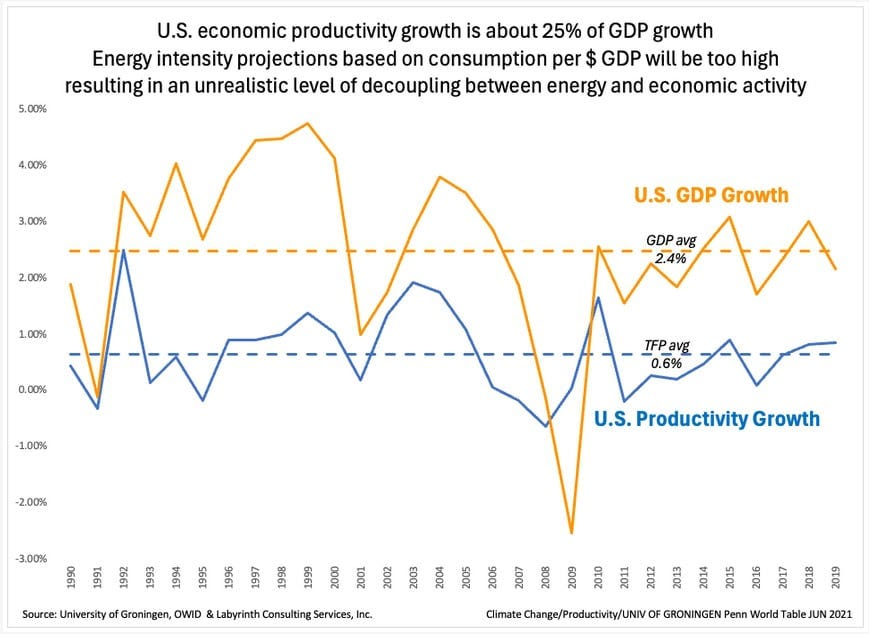

More specifically, there’s a fundamental gap between GDP and real economic productivity. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks total factor productivity (TFP)—a measure of how efficiently labor and capital are used— back to 1950. A straightforward comparison shows that productivity growth accounts for only about 25% of GDP growth (Figure 7).

This means that projections of energy intensity—based on consumption per dollar of GDP—are likely unrealistic, at least for the U.S. If productivity isn’t keeping pace with GDP, then claims of decoupling energy use from economic growth are probably more illusion than reality. The result? Energy forecasts based on this assumption overstate how easily economic activity can grow while energy use declines.

Why are there so many inconsistencies in the World Energy Outlook 2024? The data tables don’t seem to have undergone rigorous review—category totals often don’t equal the sum of their subcategories. The discrepancies aren’t huge, but why are they there at all?

It seems likely that managers compiled the report based on summaries from analysts, prioritizing high-level over detailed analysis. Without direct engagement with the raw data, nuanced inconsistencies go unnoticed. These aren’t necessarily errors—just the inevitable complexity of real-world data, which only close scrutiny can reveal.

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2024 offers an optimistic view of a smooth transition to renewables. This is at odds, however, with the realities of energy consumption, economic growth, and the hard limits of ecosystem capacity. Despite decades of investment, fossil fuel consumption remains stubbornly high, and expectations for renewables to sustain comparable economic growth are idealistic.

The IEA and many renewable energy advocates ignore the fundamental problem of “overshoot“—the reality that human consumption has already surpassed the planet’s ecological limits. The optimistic projection for a renewable energy future reflects an inadequate understanding of the past and present. The idea that renewables can sustain continued economic growth without addressing the underlying issue of excessive resource use is dangerously naive.

Economic expansion requires more than just cleaner energy—it demands vast material inputs and energy yields that renewables, in their current form, struggle to provide. By focusing only on decarbonization, these projections overlook the deeper challenge: a growth-based system incompatible with planetary boundaries. Until the obsession with endless growth and consumption is confronted, energy forecasts, no matter how green they appear, will remain built on wishful thinking

I don’t agree with those last two paragraphs at all. They are a case of a Berman falling back into his peak oil/gas negative thinking. I explained why in my editor’s note to Jim’s 2016 article:

I have been fascinated, ever since taking my first Resource Economics course course at Penn State some 52 years years ago or so, at how predictably otherwise supposedly intelligent people will always predict the exhaustion of natural resources. It’s been going on, I suppose, since the first cave man, realizing his supply of flint to make projectile points was running low, imagined there might be no way to hunt animals and supply himself with meat in the future. He couldn’t envision any other world, or bullets. It’s seemingly been going on ever since, as one “expert” after another over the centuries has predicted the end, unable to imagine the alternatives mothered by need combined with ingenuity.

Such has been the case with the shale revolution and, interestingly enough, a day after Jim put this post up on MDN, his favorite branch of government, the Energy Information Administration, came out with a great article explaining how low natural gas prices (which are a sign of surplus, not scarcity) are projected well into the future as a result of the shale revolution, providing inexpensive fuel for electricity generation while reducing carbon emissions.

And, those low prices continue to this day with natural gas, indicating there is no scarcity of the resource and no ability for solar and wind to compete absent subsidies. Putting aside Berman’s magical Malthusian thinking, though, he makes very strong points about the ridiculousness of IEA thinking.

#IEA #ArtBerman #Energy #EnergyTransition

Art is a very intelligent and very interesting guy. I’ve had the privilege of meeting him before the big green grift and we did discuss the horizontal drilling - the so called unconventionals. I also had the good fortune to talk with Michael Economides during the same time frame. But looking back in 20 years from now I suspect there will be multiple opinions about who had the more accurate opinion. There’s some strong points and truth in both. The reality is that the IEA is a grifter organization and serves no purpose useful to humankind.